News

The strangest planet in the solar system: scientists solve the mystery of Uranus after 38 years

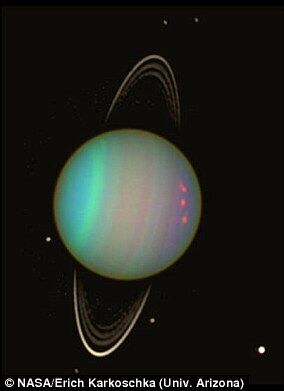

Uranus is often called the strangest planet in our solar system. But a new study suggests that the gas giant may not actually be as strange as scientists thought.

Researchers from University College London (UCL) say that the mysteries surrounding Uranus could be the result of an extremely powerful solar storm that occurred just as the Voyager 2 spacecraft visited the planet 38 years ago. Based on the findings, experts are calling for a second mission to Uranus to find out the planet's behavior during normal weather, DailyMail writes.

In January 1986, Voyager 2 flew past Uranus. This NASA probe was the first and so far the only spacecraft to explore this planet.

"Almost everything we know about Uranus is based on the Voyager 2 flyby alone. The new study shows that many of the planet's strange behaviors can be explained by the magnitude of the space weather that occurred during that visit," said study co-author Dr. William Dunn.

Scientists emphasize that with intense solar wind, observations of Uranus have led to erroneous conclusions, especially regarding the planet's magnetic field, Reuters reports.

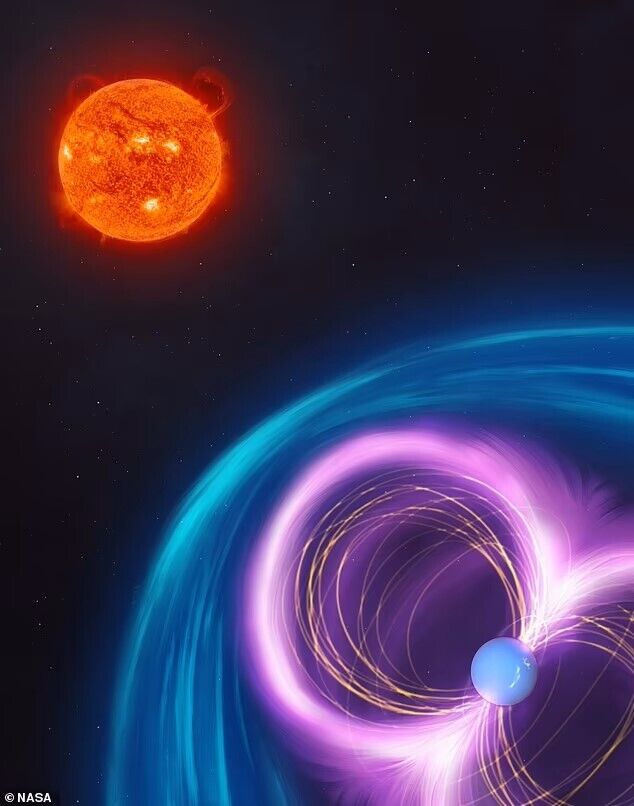

The solar wind is a high-speed stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun, scientists explain.

The researchers found that Voyager 2 encountered Uranus only a few days after the solar wind had crushed its magnetosphere – the planet's protective magnetic bubble – by about 20% of its normal volume.

"We would have seen a much larger magnetosphere if NASA's spacecraft had arrived a week earlier," said space plasma physicist Jamie Jasinski of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Scientists have suggested that Uranus' magnetosphere is actually similar to that of Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune, and other giant planets in the Solar System.

Instead, Voyager 2's observations left a false impression that Uranus' magnetosphere has no plasma, but has extremely intense belts of high-energy electrons.

The spacecraft's data also showed that Uranus' two largest moons, Titan and Oberon, often orbit outside the magnetosphere. However, the new study indicates that they tend to stay inside a protective bubble, making it easier for scientists to magnetically detect potential subsurface oceans.

Scientists are eager to find out whether subsurface oceans on satellites outside the solar system have conditions suitable for supporting life. To this end, on October 14, NASA launched a spacecraft to Jupiter's moon Europa.

Scientists discuss the upcoming mission to Uranus. "This mission is crucial for understanding not only the planet and magnetosphere, but also its atmosphere, rings, and satellites," summarized physicist Jamie Jasinski.

Only verified information is available on our Telegram channel OBOZ.UA and Viber. Do not fall for fakes!