News

James Webb Telescope solves Hubble's 20-year-old puzzle

The James Webb Telescope has solved the Hubble puzzle of 20 years ago. In a new study, scientists have found that when heavy metallic elements are scarce, planetary disks can last much longer than previously thought.

According to previous studies, astronomers were sure that the disks of dust and gas that surrounded these stars with light elements should have been blown away by the star's own radiation, dispersing the disk in a few million years and leaving nothing that could form a planet. According to scientists, the heavy elements needed to create a durable planetary disk around the star were not available until later supernova explosions created them, LiveScience writes.

The Hubble discovery

In the early 2000s, the Hubble Space Telescope observed the oldest planet in history, an object 2.5 times larger than Jupiter, which was formed in the Milky Way 13 billion years ago, less than a billion years after the birth of the Universe. Soon, discoveries of other old planets began. This puzzled scientists because the stars in the early universe should have been composed mostly of light elements such as hydrogen and helium, with almost no heavy elements such as carbon and iron that make up planets.

Confirmation with the Webb telescope

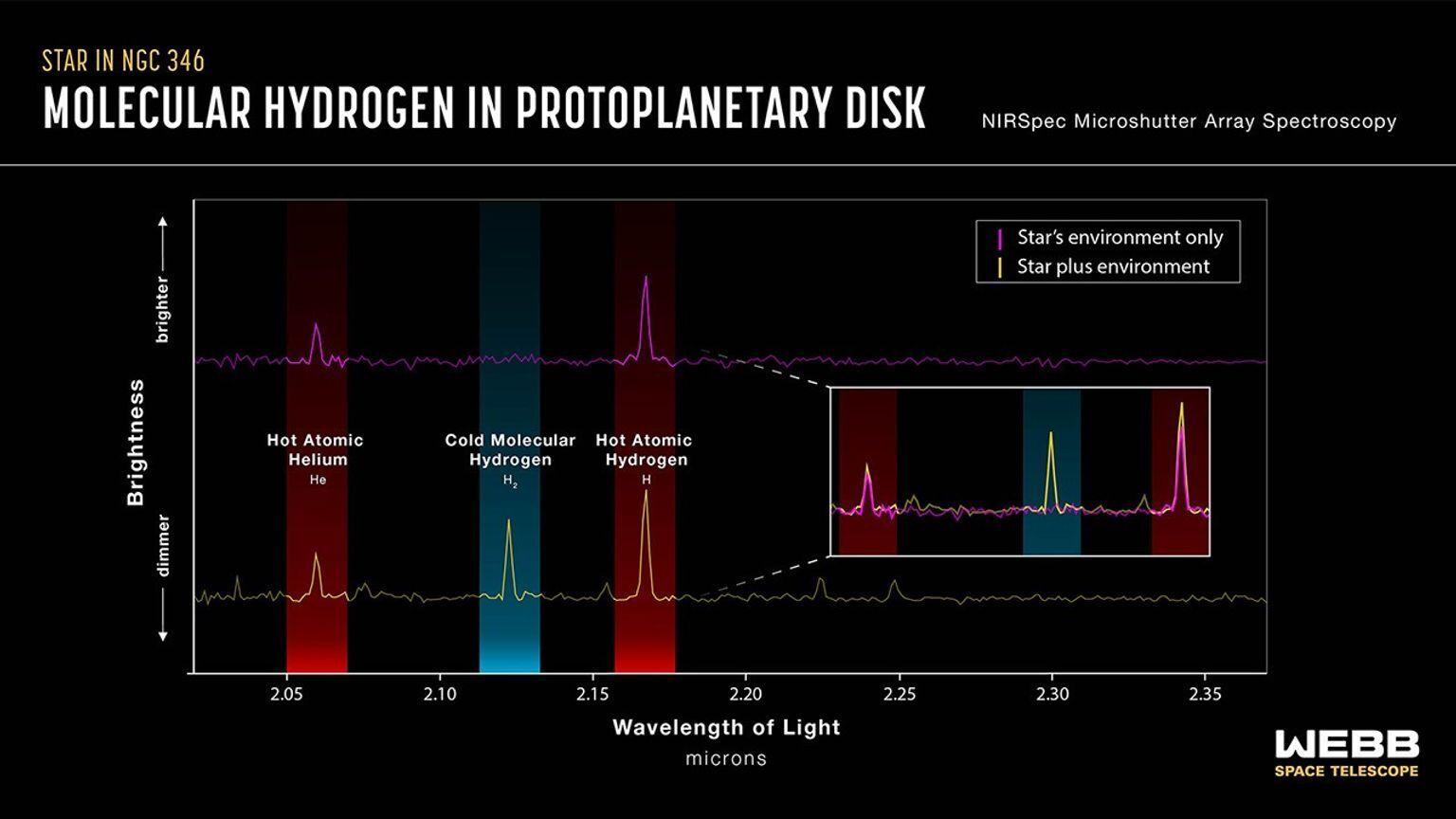

Now, however, the James Webb Space Telescope has taken a close look at a modern proxy for these old stars and found that Hubble was right. Thanks to Webb's sensitivity and resolution, scientists have obtained the first-ever spectra of the formation of Sun-like stars and their immediate surroundings in a neighboring galaxy.

"We can see that these stars are indeed surrounded by disks and are still in the process of absorbing material, even at a relatively old age of 20 or 30 million years," Science Nasa quoted lead author Guido De Marchi as saying. He also added that this suggests that planets have more time to form and grow around these stars than in neighboring star-forming regions in our own galaxy.

James Webb observations

The Webb Telescope observed spectra (measurements of different wavelengths of light) of stars in a star-forming cluster called NGC 346. The conditions in this cluster are similar to those of the early Universe, with an abundance of light elements such as hydrogen and helium and a relative lack of metallic and other heavier elements. The cluster is located in the Small Magellanic Cloud, a galaxy 199,000 light-years away from Earth.

The light and electromagnetic waves emitted by these stars and their surroundings have shown that they contain long-lived planetary disks. The researchers explained that there may be two different mechanisms, or even a combination, by which planet-forming disks persist in environments deficient in heavy elements.

First, to be able to blow away the disk, the star applies radiation pressure. For this pressure to be effective, elements heavier than hydrogen and helium must be in the gas. However, the massive star cluster NGC 346 contains only about ten percent of the heavy elements that are present in the chemical composition of our Sun. Perhaps the star in this cluster simply needs more time to disperse its disk.

The second option is that for a Sun-like star to form when there are few heavy elements, it would have to start with a larger gas cloud. A larger gas cloud would create a larger disk. Thus, the disk has more mass, and thus it would take longer to blow away the disk, even if the radiation pressure worked in the same way.

"It affects how you form a planet and the type of system architecture you can have in these different environments. And that's very exciting," said study co-author Elena Sabbi, chief scientist at the Gemini Observatory at the National Science Foundation's NOIRLab in Tucson.

Only verified information is available on the OBOZ.UA Telegram channel and Viber. Do not fall for fakes!