News

Top 6 historical mysteries scientists have solved in 2024

This year, scientists managed to lift the veil surrounding a number of historical figures. They uncovered more facts about their unique stories.

In some cases, the analysis of ancient DNA has helped to fill in the gaps in knowledge and change prejudices. CNN writes about 6 historical mysteries solved by science in 2024.

Revealing the unknown

A detailed analysis of tooth enamel, tartar, and bone collagen helped researchers uncover details about "Vittrup Man," a Stone Age migrant who suffered a violent death in a swamp in northwestern Denmark about 5,200 years ago.

His remains, dredged up from a peat bog in Vittrup, Denmark, in 1915, were found next to a wooden stick that was probably used to beat him over the head. Still, little was known about him.

Using state-of-the-art analytical methods, Anders Fischer, a project researcher at the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, and his colleagues set out to "find the individual behind the bone" and tell the story of the oldest immigrant in Danish history.

The "Well Man" from the Norse saga

Researchers have been able to link the identity of a skeleton found in a castle well to an 800-year-old Norwegian text.

The Sverris saga, which tells the story of the real-life king Sverre Sigurdsson, describes how in 1197 an army of invaders threw the body of a dead man into the well of the Norwegian castle Sverresborg, probably to poison the water in the well.

A group of scientists recently examined bones found in the castle's well in 1938. Using radiocarbon analysis, the researchers determined that the remains are about 900 years old. Genetic sequencing of the tooth samples showed that the "well man" had a medium skin tone, blue eyes, and light brown or blond hair. Most interestingly, he was not related to the local population.

Debunking the myth of the "lost prince"

Advances in molecular genetics over nearly two decades have helped researchers unravel the longstanding historical mystery of the so-called "lost prince" who appeared in Germany in the mid-19th century seemingly out of nowhere.

For 200 years, there was speculation that the mysterious man, named Kaspar Hauser, secretly belonged to the German royal family. He was found wandering around Nuremberg without papers in May 1828 at the age of 16. He could barely communicate with those who questioned him.

Several studies have been conducted on genetic data taken from items that belonged to Hauser, but conflicting results have led to a dead end with no answers. This year, researchers conducted a new analysis of Hauser's hair samples and were able to prove that his mitochondrial DNA, or genetic code passed down through the maternal line, does not match the one of the Baden family.

Although the disproval of the royal hoax solved one mystery, another arose in its place: who was this man?

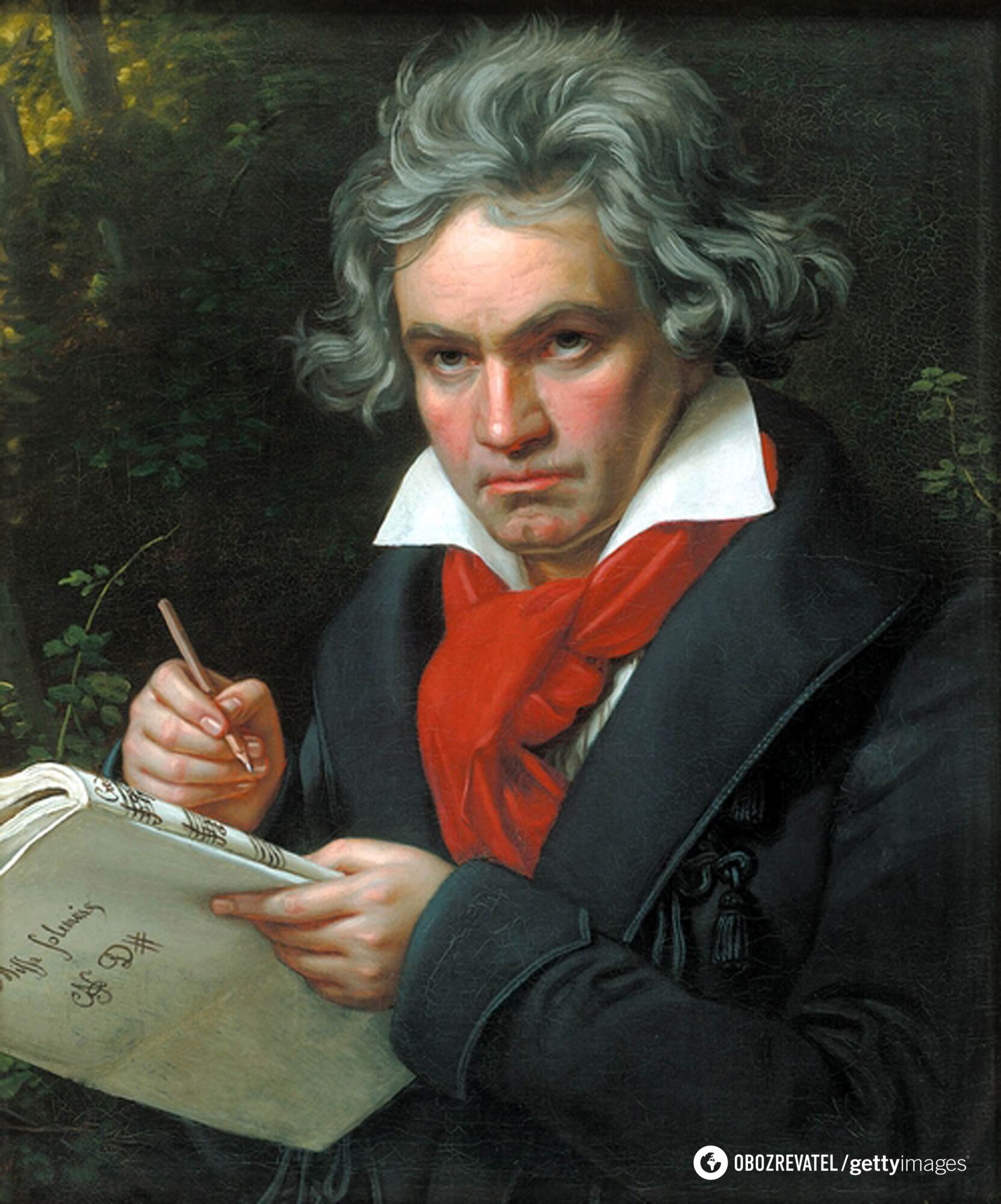

A sick and tortured composer

The classical composer Ludwig van Beethoven died in 1827 at the age of 56 after years of illness, including deafness, liver disease, and gastrointestinal disorders. The composer expressed his desire to have his illnesses studied and the results disseminated.

In May, scientists published a study that showed high levels of lead found in authentic strands of Beethoven's hair and suggested that the composer had lead poisoning, which may have caused his recurring health problems. These findings build on previous discoveries made after Beethoven's genome was made publicly available to explore the complex nuances of his health.

In addition to lead, Beethoven's locks also contained elevated levels of arsenic and mercury. Moreover, it is not known they got there. Most likely, the substances accumulated in the musician's body as a result of his lifelong consumption of fish from the polluted Danube River and tap wine that was sweetened and preserved with lead.

The new findings contribute to a better understanding of the composer's health, as well as the complex, large-scale symphonies he left behind that are still performed by orchestras around the world.

Colonial drama

The study of skeletal remains using new DNA analysis techniques shed light on the fate of family members of the first US President George Washington in March.

Washington's younger brother Samuel, who died in 1781, and 19 other family members were buried in a cemetery at Samuel's estate near Charlestown, West Virginia, according to Courtney Cavagnino, a researcher at the U.S. Army Medical Examination System's DNA Identification Laboratory. However, some graves were unmarked, most likely to prevent them from being looted. A research team has conducted excavations to find Samuel's final resting place, but the location of his grave remains a mystery.

The methods can be further used to identify the unknown remains of those who served in the military since World War II.

Meanwhile, a separate study of unmarked graves found in the British settlement of Jamestown, Virginia, revealed a long-hidden scandal in the family of the colony's first governor, Thomas West.

The researchers analyzed the DNA of two male skeletons in the graves. Both turned out to be related to West through a common maternal line. One of the men, Captain William West, was born to West's aunt, Elizabeth, and was illegitimate.

Researchers have discovered that details of West's birth were deliberately removed from the family's genealogical records at the time, and speculate that it was the mystery of his true origins that inspired him to cross the Atlantic Ocean and join the colony.

Inside the minds (and laboratories) of prominent astronomers

Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe is associated with the celestial discoveries of the 16th century. But he was also an alchemist who brewed secret medicines for elite clients such as Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor.

Renaissance alchemists kept their work secret, and few alchemical recipes have survived to this day. Although Brahe's laboratory, which was located beneath his castle residence and the Uraniborg Observatory, was destroyed after his death, researchers have conducted chemical analysis of glass and ceramic shards found at the site.

It revealed elements such as nickel, copper, zinc, tin, mercury, gold, lead and, surprisingly, tungsten, which had not even been described at the time. It is possible that Brahe isolated it from the mineral without realizing it, but this discovery raises new questions about his secret work.

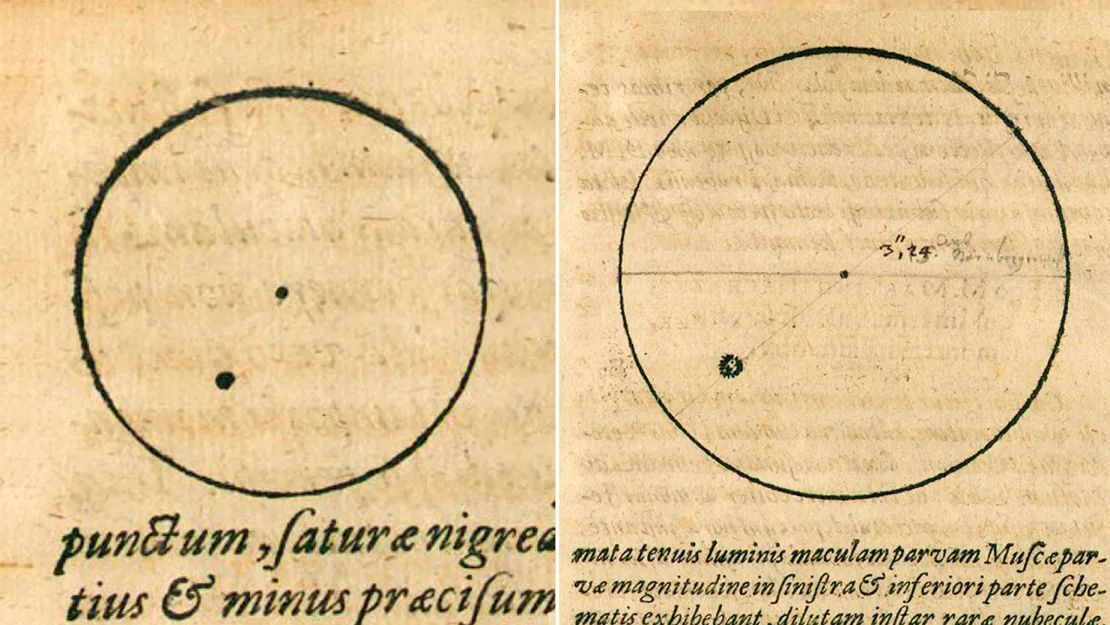

In addition, several centuries after the German astronomer Johannes Kepler made sketches of sunspots in 1607 based on his observations of the sun's surface, these pioneering drawings helped scientists piece together the history of the sun's solar cycle.

Although each cycle of solar activity usually takes about 11 years to complete, there have been times when the sun has not behaved as expected. And by analyzing long-forgotten Kepler drawings made before the advent of telescopes, scientists have learned more about the Maunder Minimum, a period of extremely weak and anomalous solar cycles between 1645 and 1715.

Kepler's drawings were made with a camera obscura, a device that used a small hole in the wall of an instrument to project an image of the Sun onto a piece of paper. His sketches depicted sunspots that helped astronomers determine that solar cycles occurred as expected when Kepler observed them, rather than lasting an abnormally long time as previously thought.

So this year, the centuries-old work of Brahe and Kepler was supplemented with new fragments that helped scientists reconstruct the mysteries of the past.

Only verified information is available on OBOZ.UA Telegram channel and Viber. Do not fall for fakes!