News

Scientists have solved the mystery behind the Switzerland-size hole that opened in Antarctica in 2016

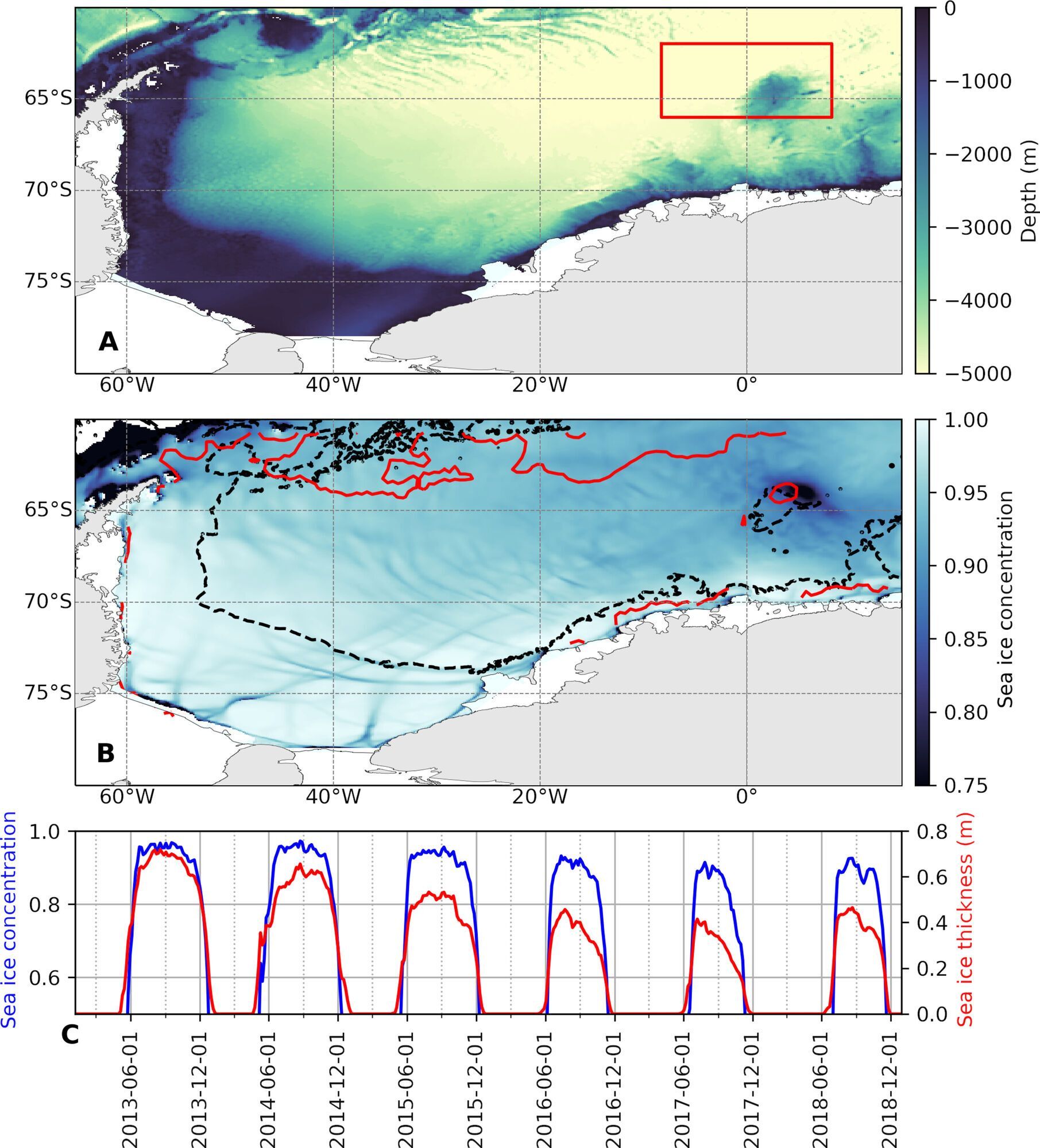

Every Australian winter, Antarctica undergoes radical changes. The sea ice surrounding the continent expands outward, effectively doubling the size of Antarctica. But in the winter of 2016 and 2017, a rare hole appeared in the middle of the sea ice called the Maud Rise polynya, about the size of Switzerland.

For all these years, scientists have been unable to find out why. And only now they have succeeded, Space magazine reports, citing a study in the journal Science Advances.

The hole was named Maud Rise because of the underwater mountain located beneath it in the Weddell Sea. According to the new study, it was eventually formed through a combination of wind, ocean currents and underwater geography that created ideal salty conditions for melting sea ice.

The Maud Rise line was first identified by Earth observation satellites in the 1970s, especially in the winter of 1974 to 1976. Scientists assumed that the line would return every winter, but this did not happen. It appeared only sporadically and for a short period of time.

In 2016 and 2017, the circular ocean current in the Weddell Sea was stronger than usual. Thus, the rise of deep water into the upper ocean layers around the Maud Rise brought warmer and saltier water closer to the surface.

"In 2017, for the first time since the 1970s, we had such a large and long-lasting polynya in the Weddell Sea," study leader Aditya Narayanan, a researcher at the University of Southampton in England, said.

Using data from satellites, autonomous floating vehicles, and sightings of marine mammals, the team determined that turbulent eddies around the Maud Rise brought more salt into the area, which was then transported to the surface through a process called Ekman transport. Due to it, water moves at a 90-degree angle to the wind and affects ocean currents.

"The imprint of a polynya can remain in the water for several years after they have formed. They can change the way water moves and how currents transfer heat to the continent. The densewater that forms here can spread across the world's oceans," research team member Sarah Gill, a professor at the University of California, San Diego, said.

Only verified information is available on OBOZ.UA Telegram channel and Viber. Do not fall for fakes!