News

Scientists have grown "mini-brains" in the laboratory and may have confirmed a key theory about autism

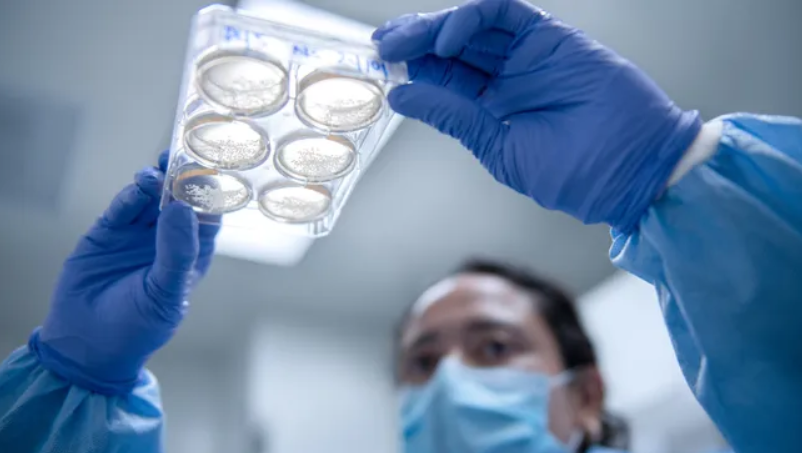

In the new study, researchers took stem cells from the blood of 10 toddlers with autism and six children without autism. Using growth-promoting chemicals, the researchers grew "mini-brains" or brain organoids from these stem cells in the laboratory.

As they grew, the organoids accurately captured key aspects of human brain development and function in the womb. Since each organoid was grown from the baby's own tissue, it can be considered a mini-version of that child's brain during the first trimester of pregnancy - as if scientists had turned back the clock on development, Live Science writes.

The researchers tracked how the size and growth of these organoids changed during the early stages of embryonic development. In addition, they assessed the severity of each baby's current autism symptoms, including their ability to pay attention to and communicate with others, their language skills, and their IQ.

The team also scanned the toddlers' real brains to check the activity of various cells, especially those in areas of the brain associated with social skills and language.

The scientists found that the brain organoids of babies with autism grew almost three times faster than those of children without autism, becoming about 40% larger between the first and second months of pregnancy compared to the control group. The researchers also noted a general trend: the larger the brain organoid, the more severe the social symptoms of autism in the child in question.

Previous studies, including those conducted by the authors of the new study, have linked an increase in brain size in the early years of life to the severity of social symptoms in people with autism. This latest study, however, establishes a direct link between symptom severity and brain size in individual toddlers, rather than highlighting trends in a group.

"These new findings add interestingly to the previous work of the study authors. The new study suggests a 'quantifiable link' between the degree of excess brain growth seen in the womb and the extent of later autism symptoms," commented Dr. Jonathan Green, a professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Manchester in the UK who was not involved in the study.

In a separate experiment conducted in the same study, the team also found that the higher growth rate and larger brain organoid size in young children with autism were associated with increased activity of a gene called Ndel1. This gene encodes a protein that helps regulate embryonic brain development, so scientists believe that it is likely that Ndel1 dysfunction is partly responsible for the excessive brain growth seen in autism.

"Determining that NDEL1 is not functioning properly was a key discovery," said study co-author and professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, Alysson Muotri.

Social symptoms are not the only component of autism. For example, many people with the condition may also experience symptoms such as repetitive behaviors, motor skill delays, and anxiety, which were not assessed in the new study. This may limit the generalizability of the results to other people.

Looking ahead, however, the team aims to identify more genes that may cause excessive brain growth in autism. They hope that one day this will lead to the development of new treatments for the disorder.

Only verified information is available on the OBOZ.UA Telegram channel and Viber. Do not fall for fakes!