News

Physicists debunked the most terrifying scene in Oppenheimer: how an atomic bomb actually works

Spoiler alert for those who haven't seen Oppenheimer: the world's first atomic bomb explodes about two-thirds of the way through the movie. Just before that, one of the physicists laughingly bets on whether it will burn up the entire atmosphere, to which the protagonist replies that the chances are close to zero.

Where did this phrase come from? Thanks to the views of a nuclear physicist and Pulitzer Prize winner, Inverse writes.

How atomic bombs work

When a uranium-235 atom absorbs an extra neutron, it becomes unstable and eventually decays. This releases the energy that held it together – with two or three wandering neutrons.

If these neutrons also hit neighboring uranium-235 atoms, and if there is enough uranium in one place under the right conditions, you get a chain reaction that releases a really terrifying, city-destroying amount of energy.

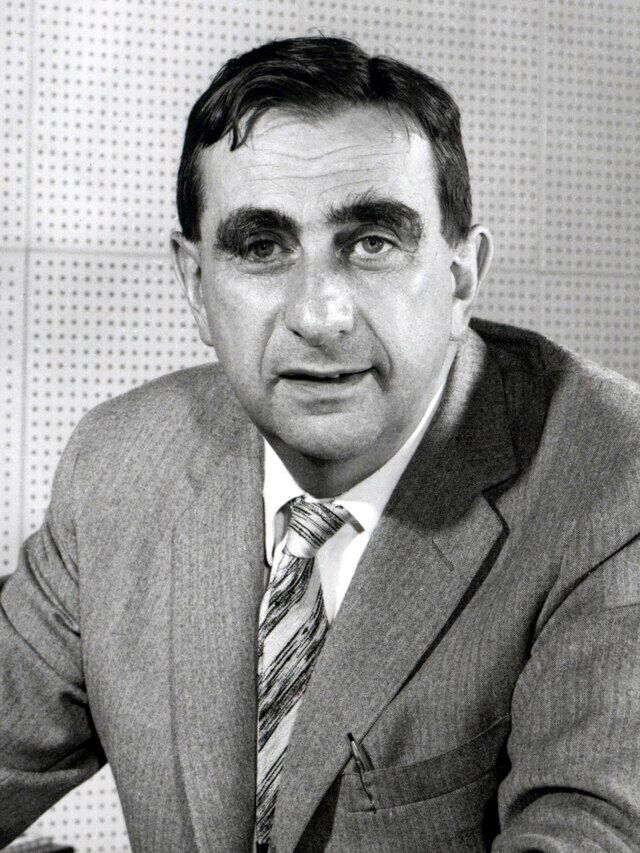

At the same time that the Manhattan Project was trying to figure out how to split enough uranium atoms at a time to make a bomb, physicist Edward Teller was working on a parallel project: the hydrogen bomb. It was supposed to use a small atomic bomb to trigger nuclear fusion in a pile of deuterium (an isotope of hydrogen).

It's the same reaction that powers the sun but in miniature. It would be another decade before the first hydrogen bomb became a grim reality, but in 1942, Teller was still thinking about how to build one.

And this made him worry for a while about blowing up the entire atmosphere. It was the same principle: a bomb powered by nuclear fission could create enough heat and pressure to trigger even more destructive nuclear fusion.

Teller wondered if the heat and power of the bomb could be enough to trigger another kind of chain reaction, in which nitrogen atoms in the atmosphere would fuse. As Manhattan Project physicist Hans Bethe later recalled, Teller posed this question at a project meeting in 1942.

"There's nitrogen in the air, and you can have a nuclear reaction in which two nitrogen nuclei collide and turn into oxygen plus carbon, and a lot of energy is released in the process. Can't that happen?" asked Teller.

They counted – manually – and found the answer

"There has never been any possibility of causing a thermonuclear chain reaction in the atmosphere," Bethe wrote in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in 1975.

"Ignition is not a matter of probability, it is simply impossible," the scientist argued.

The atoms in the Earth's atmosphere are not densely packed enough for a fusion reaction to occur. Nuclear fusion occurs in the cores of stars due to literally astronomical pressures, and this is impossible in the Earth's atmosphere. An atomic bomb can compress a small amount of deuterium in a confined space, enough to trigger fusion, but in the Earth's atmosphere, it would burn up pretty quickly.

"He didn't take into account some important things, such as how much fuel you need to not only heat but also compress," says Richard Rhodes, author of The Making of the Atomic Bomb.

On the morning of July 16, 1945, Oppenheimer and company waited for the night storm to subside. Everyone knew that the world would not be destroyed in one explosion. Fermi reportedly took bets on the subject, mostly to pass the time, but Bethe's calculations had settled the issue long before that. Nuclear doomsday was close to becoming a real possibility, but it would not turn the entire sky into a fireball from a single bomb.

The "near-zero" odds probably come from the words of Manhattan Project physicist Arthur Compton, who said in a 1959 interview that the possibility of such a development was "just under one in three million."

In 1975, Bethe denied that the probability of igniting the atmosphere was less than one in three million, but this idea has already managed to gain a foothold in the public imagination.

Only verified information is available on the OBOZ.UA Telegram channel and Viber. Do not fall for fakes!