News

More than 230 million people on Earth have a genetic disorder of "explosive" cell death

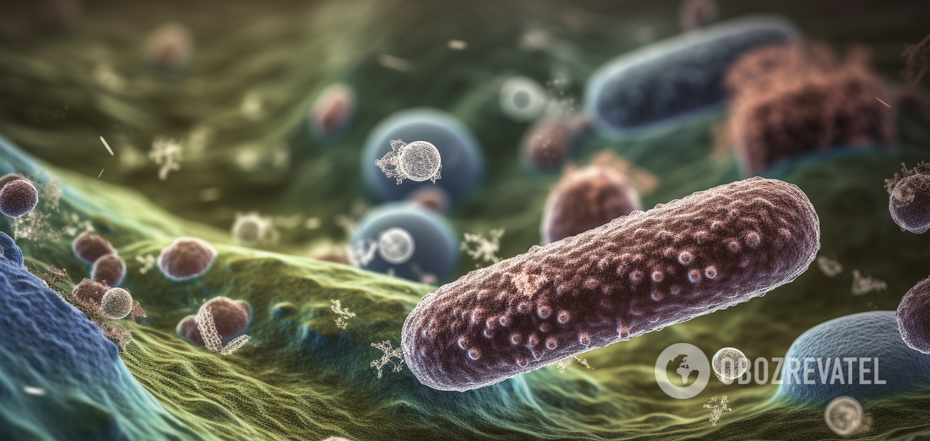

Approximately 3% of the world's population, which is more than 230 million people, has a genetic defect that increases the risk of inflammation through the mechanism of so-called "explosive" cell death. This feature of the body can lead to the development of various diseases.

This is stated in a study by the Australian WEHI Institute, published in Nature Communications. The work of scientists may shed light on why certain people are more likely to develop certain types of diseases.

As SciTechDaily explains, millions of cells die in the human body every minute. This process is important and useful because it protects the body from disease by removing unwanted, damaged, or dangerous cells. This ultimately helps prevent the spread of viruses, bacteria, and even cancer.

But the process of cell death is not always peaceful. According to the first author of the paper, Dr. Sarah Garnish of WEHI, there is a type of death called necroptosis, which is characterized by the fact that a cell that dies in this way essentially explodes, sending an alarm to other cells in the body.

"This is good in the case of a viral infection, when necroptosis not only kills the infected cells, but also gives the immune system an indication to react, clean up and start a more specific, long-term immune response," Garnish explained.

But sometimes necroptosis can be harmful. If its signal is "uncontrolled or excessive," the body itself can provoke a disease.

The main active unit of necroptosis is the MLKL gene. When the body needs to trigger a high-firepower cell death reaction, cellular brakes are activated, which eventually stop MLKL. However, in some people, these brakes are too weak.

"In most of us, MLKL stops when the body tells it to stop, but 2-3% of people have a form of MLKL that is less responsive to stop signals. Although 2-3% is not a lot, given the size of the world's population, it means that millions of people have a copy of this gene variant," the scientist said.

The study suggests that such a widespread genetic change can combine with a person's lifestyle, infection history, and broader genetic makeup to increase the risk of inflammatory diseases and severe reactions to infections.

In particular, when it comes to type 2 diabetes, its development rarely depends on a single gene change. Instead, the disease is influenced by many different genes, as well as environmental factors such as diet and smoking.

That is, as scientists explain, it is not that the MLKL gene itself provokes the body to develop a certain disease, but its combination with other factors can be dangerous.

In the future, researchers hope to pinpoint genetic changes that could mean someone is more likely to have a severe case of COVID-19 or less likely to recover from chemotherapy.

"Every piece of information like this helps us make personalized medicine more real," Garnish said.

The WEHI research team is now also trying to understand whether there is a variant where people with the MLKL gene variant may have a stronger cellular defense response to certain viruses.

Garnish noted that if such a gene is passed down between generations, it means that it also performs some currently unknown useful function.

Earlier, OBOZREVATEL reported that geneticists have decoded the last missing part of the human genome for the first time.

Subscribe to OBOZREVATEL'sTelegram and Viber channels to keep up with the latest developments.