Entertainment

Ancient myth as a warning to modernity

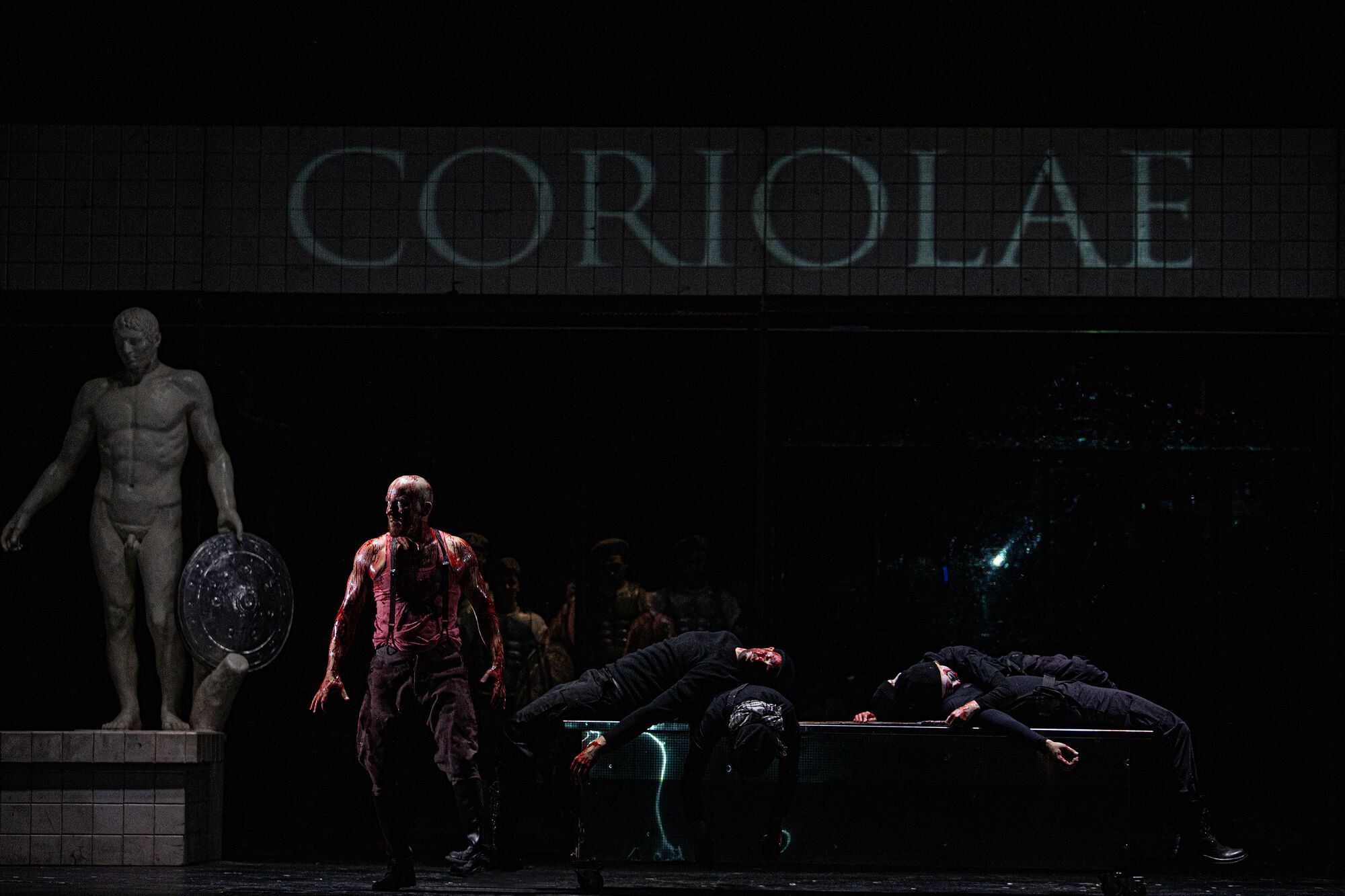

Title/author: Coriolanus. W. Shakespeare

Theater: National Drama Theater named after I. Franko

Director: Dmytro Bohomazov

Shakespeare is always a win-win. The works of the brilliant playwright are multilayered, full of aphoristic quotes, and have room for actors to reveal their talents. But it is precisely because of the complexity and ambiguity of the plays that the original meanings that were put into the performance can change to almost opposite ones. For example, "Coriolanus," about the exploits and betrayal of a Roman general, at its premiere in 2018, might have seemed like a satire of the aggressor neighboring country, whose society was imbued with the ideas of a victorious victor in the spirit of "we can do it again." Today, "Coriolanus" is a warning to our society.

Shakespeare's play "Coriolanus" has been staged for four centuries, and the legend of the general who did not find himself in politics dates back more than two millennia. Only people haven't changed since then, so the story of Caius Martius remains relevant. Ancient Rome is on the verge of another hunger strike. The people, the plebeians, demand lower bread prices. The consuls do not find a better idea than to "preventively" attack Coriolanus, the capital of the Volscian neighbors, collect tribute from them, and calm the crowd with a popular victory. The campaign is entrusted to the warlike Caius Marcius, who, after the difficult but successful capture of Coriolanus, will be called Coriolanus.

But with military victory comes unexpected responsibility – political responsibility. Everyone, from his mother to the highest Roman nobility, the patricians, persuades Coriolanus to become a consul. In the wake of his popularity, even the people prefer this for the commander. But the soldier has a complicated relationship with the people. Coriolanus was born a warrior, he fought his first battle at the age of 14, and for him, the State is the only legitimate way to fight, and win trophies and glory. Coriolanus considers the plebeians to be insufficiently patriotic for their inclination to a peaceful life; they demand bread, not military posthumous glory. Coriolanus considers even the very fact of distributing bread in Rome instead of joining the army a despicable tradition. He also despises the rite in which a soldier must show his wounds to the plebs before becoming a consul. Coriolanus sabotages the tradition because he is not sure whether ordinary Romans are worthy of the blood shed for them.

The issue of Coriolanus's pride becomes so hot that a new rebellion is brewing in Rome. In modern history, in similar cases, malfunctioning helicopters crash or private jets explode in the air. But in those days, yesterday's hero was treated humanely, only expelled from Rome. Resentful of the city for which he had decorated his own body with 27 scars, the commander returns to Coriolus to fraternize with his sworn enemy Tullus Aufidius, and become the head of the Volscian army. Now Rome will see who it has lost because of its democratic traditions and constant flirtation with the plebs.

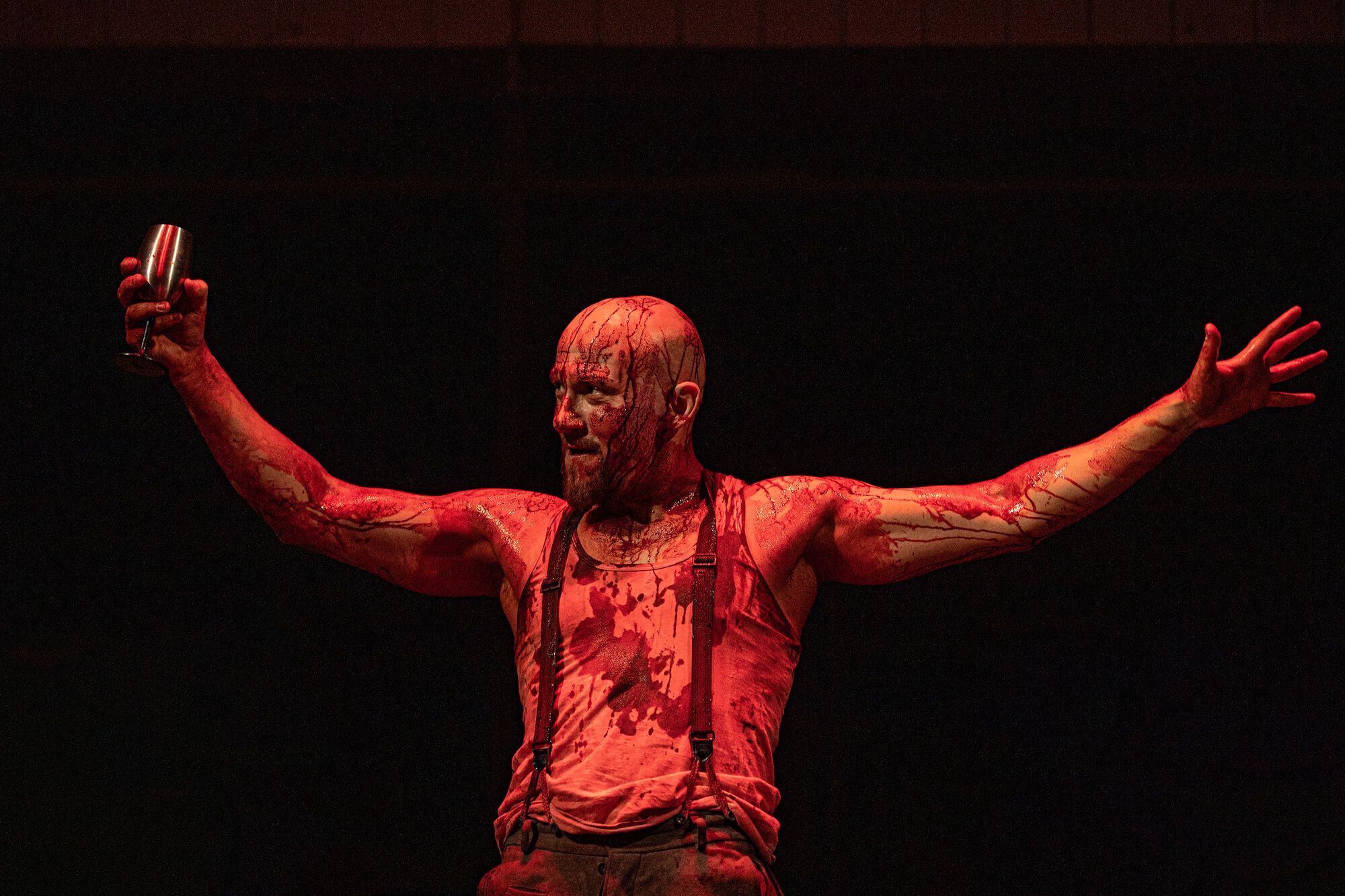

It is not for nothing that the production director Dmytro Bohomazov emphasized the red-velvet aesthetics of the postwar Soviet Union for "Coriolanus" at the Franko Theater. This is an example of a country that, for the sake of pomp and geopolitical dominance, massacred its citizens by the thousands, regardless of merit or military rank. That is why the heir to the "country of soviets," the Russian Federation, has slipped into a military dictatorship like Hitler's Reich in just three decades. The necrophilic red-velvet aesthetics of the lavish funeral were very attractive, and the shine of the golden axelbands was very dazzling. Why not repeat it?

Especially since from Coriolanus' point of view, his legend is a story of military justice. Caius Martius won all the battles on the battlefield. It doesn't matter whether he laid siege to Coriola for the glory of Rome or stormed Rome with the forces of Coriola's soldiers, the commander did not betray the god of war, did not run from the enemy, did not abandon his friends on the field, and did not renounce his principles in the corridors of power. But did Coriolanus's principled attitude benefit Rome itself, which raised him as a patriot?

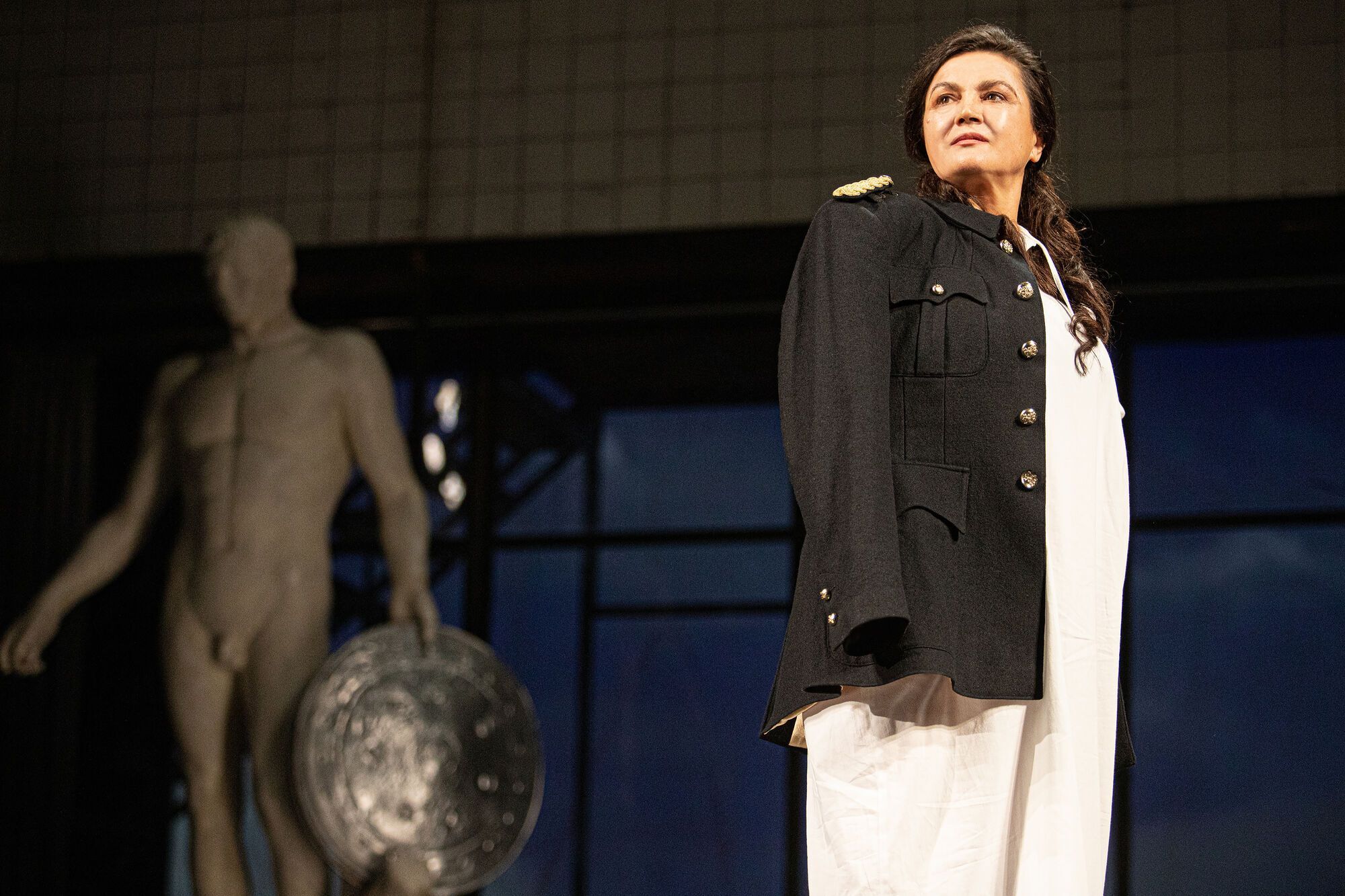

As it should be in a deep Shakespearean drama, there are no clear distinctions between good and evil. But we still see the ethics of Coriolanus himself (Oleksandr Formanchuk). That's why the patricians (Bohdan Beniuk, Ivan Sharay, Oleh Stalchuk) look slippery like reptiles, and the plebeians (Vitalii Azhnov, Oleksandr Rudynskyi, Kseniia Basha, Khrystyna Fedorak) look timid and inactive. The commander's mother (Nataliia Sumska) and wife (Anastasiia Rula) sound, though not always in agreement with Coriolanus, in unison with his ethics of military glory. And the Volscians, yesterday's enemies, with their commander Tull Avfidiy (Oleksii Bohdanovych), become Coriolanus' equal in spirit.

If in 2018, on the day of the play's release, it was easy to see parallels with the Kremlin's games, now the production may sound like a warning. The longer the war lasts, the bigger the gap between those who are on the front lines and those who are in the rear. And when the soldiers return from the front, do they see the patriots for whom they shed their blood? But the state is not only based on the military. So who should prepare for exile? Those who went to their deaths or those for whom others went?