Life

The mystery of Harriet Cole: the story of the woman whose nerves were ripped apart and shown to the world

In their desire to study the human body, scientists very often strive to cross the line to learn what no one has ever seen before. One such person was an anatomy professor, Dr. Rufus B. Weaver, who, thanks to the mysterious Harriet Cole, accomplished the unseen.

OBOZREVATEL tells the story of the creation of the first living nerve "skeleton" in human history, as well as the likely self-sacrifice that went down in the history of science.

Who is Harriet Cole

Harriet Cole, if the story that has been told for decades is to be believed, was a janitor at Philadelphia's Hahnemann Medical College (now part of Drexel University), or Weaver's assistant. She was probably African American and died in 1888 at the age of 35-40. That, in fact, is all there is to it.

Although there are dozens of media reports that she was a janitor and probably knew Weaver personally, there is actually no definitive data on this. Nor, in fact, is it 100% certain that Cole donated her body to science.

The problem is that college records at the time were not too detailed. There are indications there of a janitor or janitor's salary, but there are not even initials, let alone a whole name.

Researchers trying to find the truth about this story found a census entry from 1870 which indicated that Harriet Cole lived in the same county where the college was located. They also found information about Harriet Cole's death in March 1888, and the "place of burial" was listed as Hahnemann College. That is, her body was indeed donated for research. But did she knowingly donate it to science and was she aware of Weaver's existence? There is no data on this.

In those years, there were no laws regulating the use of cadavers for scientific research in the United States, and therefore no documents about this exist. In fact, anatomy as a science was only in its infancy and it is unlikely that there were many people willing to bequeath their bodies for autopsy back then.

However, of course, such a possibility cannot be ruled out. One version, which suggests that Cole was working at the college, is that Weaver's work struck her so much that it served as a reason for her self-sacrifice.

A more down-to-earth version is that Cole was poor, so she might as well have given her body to science in order not to burden her family with funeral expenses.

It is also possible that the dead woman's body was simply not taken, so the university bought it back.

At worst, it could be that a black woman's body was stolen or secretly sold to doctors, knowing that no one would investigate such a case.

But at the end of the day, it all comes down to the lack of any documentation to support any theory at all.

Nor have any of Weaver's personal notes or diaries been found, so the professor is unable to shed any light on the mystery.

Drexel University also admits that there are many dark places in the story that make it impossible to speak of its authenticity and writes that "all human remains deserve respect and reverence."

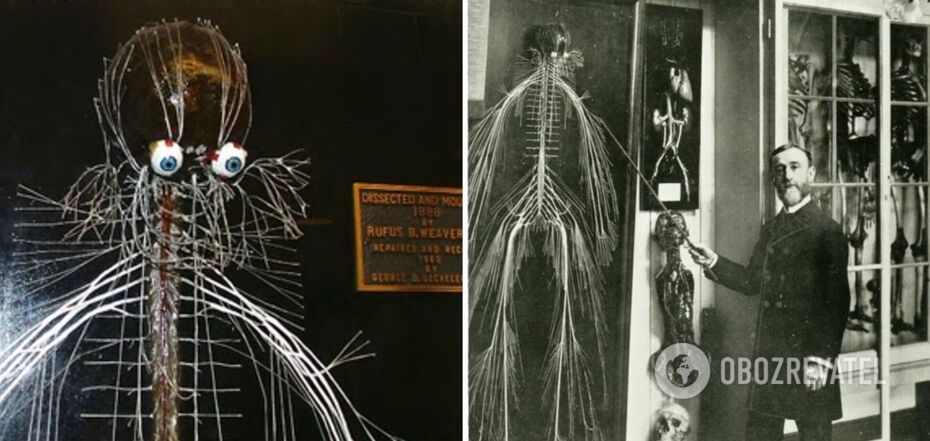

"The archival holdings of Drexel University College of Medicine contain a complete dissected specimen of the human spinal nervous system created by anatomist Dr. Rufus B. Weaver in 1888. By then this specimen was recognized as an important textbook in the field of neurology, and over the next century it became known throughout the medical world as the Harriet," according to the university website.

An 1888 death certificate indicates that the dissection was named after "Harriet Cole, the black woman whose unclaimed body was taken to Hahnemann College."

In 2018, the university set out to find out the facts about "Harriet," but since then, scientists have learned nothing new.

Rufus Weaver and the "skeleton" of nerves

As for Weaver, he began working in the field of anatomy at the end of the American Civil War. At that time his father, who was also a scientist, was engaged in identifying the bodies of fallen soldiers buried in mass graves. When his father died in a railroad accident, however, Weaver continued his work.

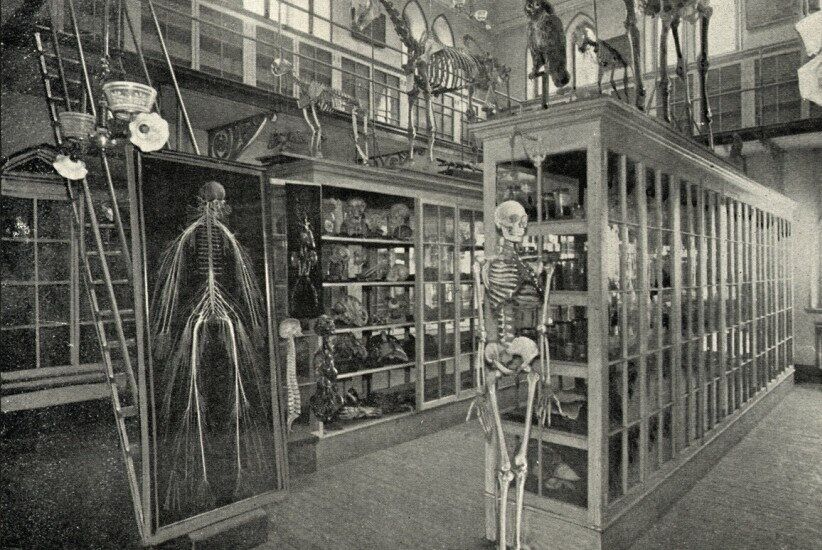

He arrived at Hahnemann College in 1879, when he accepted a position as demonstrator and teacher of anatomy, which involved dissecting corpses with students.

In 1888, Weaver obtained Cole's body and conceived the idea of creating something no one had ever seen before. He performed the first ever surgery to remove and further mount an entire nervous system.

Weaver removed nerve after nerve with extreme precision, and then wrapped each one in gauze and covered it with lead-based paint, which allowed the nerves to be preserved until modern times. He then assembled all the nerves into a single system along with the eyes.

The whole work took the doctor about five or six months.

At first the colossal exhibit was used to teach students, but when Weaver's colleagues learned of it, they called his work "a miracle of patience and skill in dissection, the likes of which had never been seen before."

Subsequently, Harriet was exhibited around the country until the 1960s, when it returned to Hahnemann College, where it is still part of the exhibit.

After Weaver, a similar operation was performed only three times.

Earlier OBOZREVATEL told about the first ever DNA photo and who took it.

Subscribe to OBOZREVATEL channels on Telegram and Viber to keep up with the latest news.